31 AUG 2008

How has your first book changed your life?

104. Kate Greenstreet

Before I ask you about your first book, would you say a little about these first-book interviews?

I was blogging and wanted to talk about new books. Two that I happened to be reading and enjoying were first full-lengths by poet bloggers Shanna Compton and Stephanie Young. It occurred to me that I could interview the authors instead of trying to write critically about their books. Much easier, more fun! Also, my own first book was due to come out later that year and I wondered what would happen when it did. What had other people experienced?

I made a list of questions. I asked Stephanie and Shanna about doing an interview--I'd had a few exchanges with each of them already because of the blog connection, so I didn't feel hesitant to ask. They both said yes, and that's how it started. I thought I'd do a few, then I asked some other poets and I thought, well, maybe ten, or twelve. But suddenly the world was full of interesting first books...

Soon poets were emailing me to see if they could be part of the project. I liked being contacted by people I didn't know--and whose work I didn't know--because the mix of styles represented became more varied. I was introduced to a lot of writers I might not have heard about otherwise and got turned on to work I would've missed.

My book came out after I'd posted 32 interviews. I kept the project going until I thought it had reached a natural conclusion, about a year after that. By the time 103 poets had responded, I figured I knew what I hadn't known when I'd asked the questions originally. But of course every poet would have a different story, so I was pleased when Keith Montesano wrote recently to ask if it was okay with me if he started a new first-book interview series, using some of my questions.

A lot of people asked me if I'd answer my own questions. (Keith asked me too.) I meant to do this months ago.

How did your manuscript happen to be picked up by Ahsahta Press? Had you sent it out much previously?

The day after I felt that case sensitive was finished, I sent it to Ahsahta Press. This was during their open submission period, so the only cost was the price of postage. For several years before that, I'd been sending out a different manuscript, Leaving the Old Neighborhood, and I spent a decent amount of money doing so. Right, some would say an indecent amount, but I don't regret the way I spent that money. For me, it was a form of tithing.

Though I'd been submitting to journals since the turn of the century, when Janet Holmes emailed to say that Ahsahta was interested in case sensitive, I'd only had five poems published. (This was July 2004.) Maybe a month or so later, Colleen Lookingbill saw two of my poems in the since-disappeared can we have our ball back? and invited me to submit a chapbook manuscript to Etherdome Press. I dismantled Leaving the Old Neighborhood to make Learning the Language, which Etherdome published in September 2005 (a year before case sensitive came out). Mainly to sell the chap, I decided to put up a website. Web design is one of the things I do for a living, so making a little site wasn't hard. I told myself I would go out and read from the chapbook that fall, but I didn't know anyone or have any idea how to start to get readings, and really I was too afraid to try. Instead of going out, I started a blog.

A lot of poets have the idea that it's impossible to get a manuscript published without connections. I remember thinking I might need to take out a loan and get into an MFA program to figure out how things are accomplished in the outside world. Then I got the email from Janet. She had never heard of me or my work--she just liked the manuscript. It was the same with Colleen. That may be rare but it can happen. (Years later, I did take out a loan--to make some repairs on our old house. Then I spent it instead on an extended book tour, but that's another story.)

Were you involved in designing the cover?

I designed the cover with Max, my husband and partner-in-design. He took the photograph on the front and the author photo.

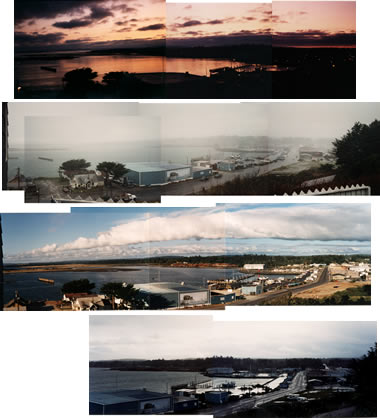

In the early '90s, Max and I lived on the southern Oregon coast. He had a habit of shooting a certain panorama--he'd be in the kitchen, look out the window, and suddenly feel compelled to go outside and take those photographs again. The prints would come back from the lab, he'd piece the view together, and shake his head, not knowing what he was after.

[click on the picture set to see them larger]

There's a single shot he took through the kitchen window soon after dawn, when the scene had so little color information that the print looked like an old brown-tone. That photo is a favorite of mine and I chose it for the front cover because I thought it could represent the imaginary town that (to me) is practically a character in the book.

How did you feel about your book's page design?

I love the way the text looks. People often mention how handsome the Ahsahta books are (the New Series and the Sawtooth Prize winners) and one of the things that makes them stand out is that their interiors are designed by Janet Holmes. Her work is inspired and impeccable. I think she did an especially wonderful job on case sensitive.

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the first time?

I wasn't happy. As soon as I took a copy out of the shrinkwrap, there were fingerprints all over the black. The surface seemed "oversensitive." Also, I'd grown attached to a test print we had made at home, even though I knew that the cover would look different. It wound up browner, had less contrast--it was a step more understated. Holding the book, I felt a drop rather than a lift. I put it back in the box and didn't touch it again for a week.

Honestly, I think the main thing going on was this: I'd felt so incredibly lucky to have a book coming out and to be published by Ahsahta that, when things kept going right, I began waiting for something to go terribly wrong. When the cover wasn't just how I'd imagined it would be, I wasn't "disappointed." Instead I kind of lowered down inside and set about "adjusting to my fate."

Over time I could see that the way the cover turned out was much better than the inkjet print we'd made. I've looked at them side by side and the real one--well, it just feels more real. More rich, more through-a-glass-darkly. More right.

After the first thousand copies sold, the second printing was done POD instead of offset. The next 200 covers were lighter, slightly redder, and printed on glossy stock. I was miserable! And though neither pals nor strangers shared my dismay, my publisher agreed we could do better. The next 200 were made from a new PDF and I'm pretty happy with the outcome: the surface is matte again but a different finish, the black somewhat "held back" but nicely resistant to fingerprints.

After case sensitive came out, I remember thinking that once a book exists as an object, it can't be everything it might have been. It stops carrying potential--it's done. But a funny thing I'd discover about a book (and its cover) is that it's not actually done on the day the new books arrive at the author's house. Months later, when a student handed me his copy of case sensitive to be signed, the cover bent and battered from use or rough traveling, the white spaces around the text sprinkled with his intriguing marginalia, I thought of my concern about fingerprints. Sure, fingerprints would mar a cover if a book were meant to do nothing but lie meekly on a coffee table. But books are made to be read. It's the reader who actually finishes a book, who allows it to become whatever it can be. Turns out it's even the reader who completes the cover design.

I watched my reading copy (the very one I cut from its shrinkwrap the day that first package thumped onto our porch) continue to change, to age or "ripen," as the tour stretched back and forth across the country. A year and a half after the book and I had our initial introduction, I accidentally left my reading copy under a seat in the auditorium following a gig in Lincoln, Nebraska. I didn't notice it gone until Max and I got back to the motel at the end of a night of mild carousing with the Lincolnians, the hall long since locked up tight. I had a box of books with me and could've easily abandoned the old one, left it for a janitor to find. Instead we set off a couple hours later than expected on the next day's seven hour drive to Tulsa, having waited for a museum guard to arrive and let us into the Sheldon to retrieve that copy. As we traveled west on I-80 out of Lincoln and I held my lost book in my hands, it never looked so good. In a way, that was the day when I saw my book for the first time. And I felt great.

Before your book came out, did you imagine your life would change because of it?

I wanted my first book to make a huge difference to me. I wanted my life to change in a big way, but I didn't know if it could.

How has your life been different since?

Before, I was completely reclusive. I worked mostly at home and didn't go anywhere if I could avoid it. But after case sensitive came out, I went out with it. I traveled to faraway towns, I met a lot of poets, I read in front of audiences large and small. To do that, I had to turn myself inside out. I guess one of my goals is to be fully reversible. I'm working on it.

What influence has the book's publication had on your subsequent writing?

Now I seem to think I'm a writer.

Were there things you thought would happen that didn't? Surprises?

I think the biggest surprise (and it kept happening and I kept being surprised) was that so many people would respond so generously to my work, and to me.

The people I've met in the past few years (including some I still only know through email) have been fantastic--open and helpful and funny and good. Overwhelmingly so. As a group, we poets might not be the most socially relaxed types, but I encountered incredible neighborliness out there, regardless of poetic factions. And I made some good friends.

What did you do to promote the book, and what were those experiences like for you?

Not counting the days of just traveling, I did 80 days of readings or class visits or both, hitting schools, bars, bookstores, gallery spaces, living rooms, and theaters in 28 states plus two cities in Canada. I was surprised to feel (I mean physically) that I had something to give--and something to receive--and to realize there was only one way that this exchange could happen: in person.

Visiting classes and workshops turned out to be something I especially enjoyed. For one thing, it's pretty amazing to sit with a group of students who have actually read your book and discussed it. (While I was writing case sensitive, the idea that the book might be taught never occurred to me.) Sometimes students had questions. Sometimes they read their work to me. Once they read me my work. They recommended books they loved. Occasionally we'd get into some hot debates. And they were just fun to hang out with.

But what else about promotion? I started a blog and posted every other day for more than two years. Illness derailed me at that point. While I was recovering, I saw that something in my schedule had to give and I decided to let the blog go. For now, at least. But the practice of keeping the blog--a place where I could experiment in public, interview others, and offer a regular greeting to anyone curious about who I might be--that was important for me. Being part of the blogging community was vital. The internet is where I come from as a poet. If I'm a regional poet, it's my region.

How do you feel about the critical response to the book?

The critical response and the personal responses I've gotten at readings and by email have been tremendously encouraging. People have read the book in fascinating, unexpected ways. I'm grateful.

Oddly--is it odd?--the book was frequently misquoted in reviews. Does this happen much to other poets? I've never heard anybody mention it.

What was the best advice you got before your book was published? Is there any advice you'd give?

The best information I got came from the people who took part in the first-book interview project. Shanna Compton was an inspiration and a big help to me when I was first trying to figure out how to get readings.

Advice I'd give? Don't wait for anybody to tell you when to do things or how to do things. If you need to know something, ask and be specific. If you need permissions or blurbs, start early.

Do you have anything else to say about touring?

Well, even though a chain restaurant like Applebee's goes to some lengths to maintain uniformity, you can't count on their Perfect Margarita to be exactly the same in every location.

One thing about trying to get a gig: some curators are happy to be contacted, others aren't. There are those who really want to do the contacting themselves. I still don't know how you can tell which are which. When I had the feeling I shouldn't ask, I mostly didn't. Sometimes I wasn't sure and gave it a try and sometimes people didn't answer.

I wasn't ingenious enough to think of it beforehand but in the course of doing all the first-book interviews, I made the email acquaintance of poets in many other places. Later, when I was trying to put together a string of dates, I could write to a poet located in a part of the map I might be passing through and ask, "Is there a reading series in your area?" Sometimes that person had started a series. Sometimes I was invited to visit a class they were teaching or to read at their house, or I was given the name of someone else I could contact. Sometimes I was offered a couch to sleep on. Sometimes a person didn't have any leads but said that if I came through their town they'd like to get together for coffee or dinner or something.

On the other hand, openly attempting to get readings doesn't fit in with everybody's notions of appropriate behavior for a poet. Some will react coldly to such a display of ambition. And if you do manage to get around, there'll be a few folks who will resent you for that, like now you might be "getting too much."

Touring to promote a first book of poetry is probably a crazy thing to do unless you have some kind of need to do it, or at least a powerful urge to find out what could happen. Most people can't get away much anyway, they have a regular job or kids or other obligations. They're not willing to spend the money, they don't have the money and aren't eager to go into debt to travel from town to town selling three books here, two books there.

But, if you want to do it, I recommend going with a buddy, a mate or fellow poet, if you can. For me, that made touring possible, period. Also it's good to have a pal who will handle the selling of your book. Left alone with the books, I just give them away--but it is nice to have that gas money.

I'm really glad I toured. I want to do it again when my next book comes out. I didn't find it easy. At home, I got off on the logistics, standing in front of the map in a kind of trance. I'd come out of the office and say to Max, "You'll never guess what she's done now," because the part of me that was arranging the dates felt completely separate from the me who would have to go do it. When we were out on the road, sometimes I really did not want to leave the motel room. Truth is, I never wanted to leave the motel room. But I got better at ignoring my resistance. And each "appearance" had at least one good aspect or outcome. Even the time we drove for hours through that blizzard...

The three of us, Janet Holmes and Max and me, set out early, hoping to beat the storm, hoping the forecast was exaggerated. It's mid-April. Maybe a third of the way between Ithaca and Albany, the falling snow begins to thicken. Soon we're passing more and more cars and trucks that have slid off the highway to the embankment or the median. The traffic has moved into a single lane, as the rest of the road fills with ice and drifts. The wipers can no longer clear the windshield. And I'm a wreck, saying (over and over) Let's just pull over... Oh look! there's a Days Inn... There's a Super 8! Max is driving, not unafraid, but fanatically committed to delivering us as promised. He says, "No, let's keep going" in a voice that I take to mean I'm trying to concentrate. So everyone is crawling along way too fast, too close to avoid a crash if somebody brakes. Just when I think I can't take it one more minute, Janet, from the back seat, as if she's thought of an entertaining story to tell us, says, "Complacencies of the peignoir, and late coffee and oranges in a sunny chair, and the green freedom of a cockatoo upon a rug mingle to dissipate the holy hush of ancient sacrifice." The atmosphere--maybe the light?--shifts. She continues. She's reciting "Sunday Morning"--you know, the Wallace Stevens poem? It's really long and she has it all by heart, and beautifully. Right around "Stilled for the passing of her dreaming feet" I notice that my body is relaxing. It seems like a miracle: I've fallen into the spell of her sound.

After the Stevens (this actually was a Sunday morning), she gave us some Yeats. The weather appeared to be improving. The snow eventually eased up and we got where we were going. We weren't late, or dead, and three curators were there along with three of us readers and Max and one audience member. Actually there were two audience members at first but, five minutes into it, one of them rushed from the room as though remembering a previous engagement. Everybody read strong, our hosts were amusing and cool, and Shafer Hall and I traded books. Afterward, most of us walked up the slushy sidewalk and around the corner to a cozy restaurant, the food was good and we laughed a lot.

Even in a chain restaurant like Chili's, the Presidente Margarita will be prepared a little differently in each location--did I mention that?

Do you want your life to change?

I want what I imagine every artist wants: to be able to support myself with my own creative work. I wish Max and I could get by with no clients but ourselves. That's not likely to ever be the case, but it's a goal. And I'd like to feel more at home in the world. That's the plot.

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

The KickStart MoneyMaker Pump is a manual treadle pump that will direct water to where it is needed, pulling water from a depth of 23 feet and lifting it up 46 feet from the source. No fuel or electricity is required to operate the pump, which can irrigate a two-acre area over an eight-hour period. There are an estimated 45,000 households in Africa running profitable small farm businesses using the MoneyMaker pump to irrigate their fruits and vegetables during the dry season. (Women entrepreneurs manage more than 50% of these farms.) By greatly increasing the yield, producing higher-value crops, and growing year round, families have been able to lift themselves out of poverty. These pumps--durable, easy to use, relatively inexpensive--have dramaticaly altered the course of many lives.

You can take all that as a metaphor for how poetry could create change. The pump doesn't guarantee success and it isn't free. Stop by the KickStart website (www.kickstart.org) to see what they're doing to make the world better.

:

2 poems from case sensitive by Kate Greenstreet:

I want you to see me

A crime had turned me into a phone. I tried to get sympathy from Michael but he thought it was funny. It hurt to laugh, but I had to. My receiver was transparent. I kept saying but Mike, I'm a phone. (I was still a person, in a way. I still had my legs.)

It was on the level of having a terrible deformity, or only one purpose (and not one I chose). I wanted him to care, but he was being so Mike. There was a flag or something patriotic on me--imprinted, near the dial. Red and blue and the white of my transparency. I couldn't even be a regular phone.

If water covers the road

It's something about living on a former

airforce base in winter

in the desert, after they've all gone.

You can't help thinking of them during the days.

Going out or coming back,

waiting. The soldiers.

They're everywhere, and mostly

I don't know their names.

I asked a man in the hardware store for help.

"The only thing you want

to remember," he said,

"about the dead

is that the bottom

of everything is theirs.

The bottom of the river, the bottom of

every drawer.

If water should cover the road,

the bottom of that puddle belongs to them."

We're in the midst of letting go.

Knot by knot,

finger by finger.

Becoming one

of the three or four people

we might have been.

You can't always walk away.

"You can think about it," he said, "but

don't believe in it: on the earth

already means under the sky."

. . .

next interview: Anne Boyer

. . .